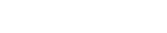

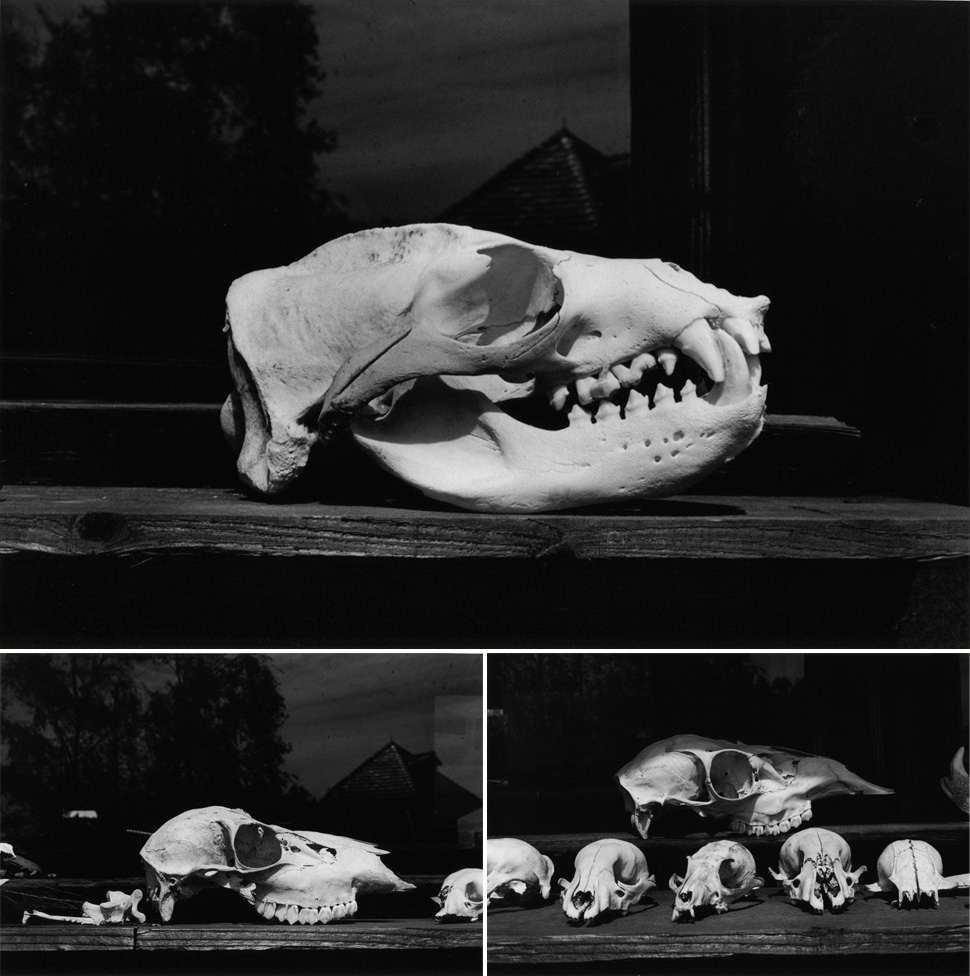

サンフランシスコのゴールデン・ゲート・ブリッジを渡って、海のほうに車で2時間ぐらい走ったボリナスという街に住むロイド・カーンの家で撮影したものです。彼がどんなライフスタイルなのかということを、『HUGE』の取材で訪れました。広い敷地に点々と家が建っていて、その中には編集室の家があったり、テラスハウスがあったり、納屋があったり。その家の至るところに動物の骨が点在しているんです。彼は『ホールアースカタログ』とか『シェルターマガジン』を作りながら、自分で本を作り、自分で家を建て、自分の中に感じるものをとても大切にしている人。彼の家はシェーカースタイルの建築で、自分もいつか家を作るならシェーカースタイルがいいなと思っていたので、なぜその建築にしたのか聞いたんです。彼が言うには、シェーカーハウスはとても機能的で、メンテナンスがすごく簡単だ、と。彼は実存主義というかミニマリズムなんですよね。自分の身の周りにある現実的に存在する確かなものがほしいだけなんだと思う。だから、骨に関しても同じで、自然界にあって人間にも備える身近なものなのに、こんなに不思議でフォトジェニックなものがあること自体が面白いな、と。ロイドの家の中は特におしゃれでも何でもないけど、自分で拾って見つけてきた骨を散りばめて置いてあるだけでこだわりを感じるし、そういう人生っていいなと思う。東京は与えられた情報が多すぎて疲れちゃうんですよ。自分は湖と森に囲まれたところに住んでいるんですが、自然なものが身近にとても多いから、例えば湖の光の綺麗な時間とか冬の森がこんなに綺麗なんだ、ということを日常の生活で感じることができる。それこそ、アーヴィング・ペンも昔から骨を撮り続けましたよね。自分が若い頃は被写体としての骨が面白いことはわかっていたけど、なぜそんなにペンが骨に惹かれるのかという理由がわからなかったんです。もちろんペンも、セザンヌや多くの画家たちからインスパイアされているとしても。でも、自分の撮った骨が何の動物のものなのかはわからないけど、そのものの一生であって、大切にできるものと思えるようになりました。もしかしたら、骨からその人生を共有している気持ちになるのかもしれないです。

I photographed these at Llyod Kahn’s home, who lives in a town called Bolinas, about two hours toward the ocean, after crossing San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. I looked into what kind of life style he led for a report in “HUGE.” In a spacious building site, there were houses built here and there; within that there was an editing house, a terrace house, a shed… And where all of these houses stood, there were animal bones scattered about. While he was making Whole Earth Catalogue and Shelter Magazine, he made books by himself, built a house by himself; he is someone that treasured anything that resonated with him. His house was in the architectural Shaker style, and I thought that I would like the Shaker style as well if I were to ever build a house, so I asked him why he chose this particular architecture. He said was that a Shaker house is very functional and the maintenance is very easy. He’s an existentialist, or rather a minimalist. I think that he only wants things that realistically exist around him. So that is why, it goes the same for bones, while it is something that provides us and is so close to humans in this natural world, it is fascinating that it is so mysterious and photogenic. The interior of Llyod’s house is not particularly fashionable, but I notice a sense of awareness of how he places bones he found, and I envy that sort of life. In Tokyo, you tire from all of the information you are given. I live in a place surrounded by lakes and forests, and because there is so much nature at hand, I can appreciate for instance the time when the light of the pond is beautiful, or how beautiful the forest is in the winter in my everyday life. And as a matter of fact, Irving Penn continued to photograph bones for a long time. When I was younger, I understood the appeal of bones as the subject, but I did not know the reason why Penn was so drawn to them, even though Penn must have been inspired by Cezanne and many other artists. I do not know what animal the bones I photograph belong to, but I have been able to think of it as important as something that reflects a life. Perhaps, I feel as though the life is being shared through its bones.

LEFT: Yasutomo Ebisu 戎 康友「Bones #9」2012, / RIGHT: Yasutomo Ebisu 戎 康友「Bones #17」2012,

基本的にポートレイトは、質感だったり髪型やフォルム、その人の体がどういうものか、どういうフォルムをしているか、とかを踏まえて、そうだとしたらカメラ位置はこうでないといけない、とか。そういうものが写らないとポートレイトとして成立しないと思う。自分の実家は写真館で、小学校2〜3年の頃、自分の親父がある日ある写真賞のトロフィーを持って帰ってきたんです。いいことがあったんだなと何となく思っていたんだけど、その賞を取った写真を改めて思い起こすと、被写体がベレー帽を被ったおじいさんだったので肌の質感があったり、その人が胸に勲章を付けていたりするのを子供心に覚えていて。自分が写真を撮り始めた20代の頃はポートレイト以外でも何でも撮れたんですが、ファッションとか広告とかCMとか、いろんなものに対してどういうふうに見たらいいのかなと考えた時に、自分は写真館で育ってきたから、ポートレイトや肖像写真を撮っていくほうが納得がいくなと思いました。今でもずっと感じていることは、本当は写真の中に何か1つのものが写真的に写っていることが写真だということです。肌質とかフォルムとか、その人の目の表情とか、1つのものがちゃんと写ることを追求していくと、1枚の写真の中で確実に完成度が上がるということに気づいたんです。たとえば、アーヴィング・ペンのタバコのシリーズは、50年代に道に転がっていた誰かの吸ったタバコに、いろんな背景が感じられて、きちんとした質感とともに写っていて、ライティングも含めて邪魔するものが何もないですよね。アヴェドンによるマリリン・モンローも、一番うつろな目をした写真を彼が選んだのは、そういうモンローを誰も見たことがないから、という裏側があったからだと思う。そういうことを常に考えています。もちろん仕事にはいろんな要素を複合させて盛り込まなければならないけど、根本的にはポートレイトはそういうふうになるといいかなと思っています。骨にはそういった写真的な要素がとても多く内包されているんです。そういう意味で、骨がいろんなことを考えさせてくれるきっかけになりました。レンズ面と角度を変えただけで違って写ってきたりもするし、自分の習作(STUDY WORK)の対象物として骨と向き合っている時間がとても面白いです。骨は人間ではないけど、被写体としてのキャラクターが滲み出ていると思う。

ここ数年、すごくわかったことがあって。撮る前から仕上げのことまでイメージして撮っているつもりですが、自分の見た目とそれがプリントとしての平面になったときの写真的な魔法があるということ。自分が想像している部分を完全に越えているアナログでしかなり得ない写真のディテールの美しさが魔法だと思う。撮っている時にはいろいろ考えるんだけど、そのアイデアを越えているんです。それがアナログの面白さ、美しさだけど、デジタルはそれが一切ない。アナログは魔法のプラスの部分を信じて写真を楽しめるようになっているから。デジタルは、アナログ的に近づけることはできても、その数値的な作業が写真家として一番面白くない(笑)。アナログだと、奥行きがどうとか、いろんなことを想像しながらファインダーを覗いて撮っているんだけど、二次元に変わる面白みの感覚を共有している人は意外と少ないような気がする。なぜなら、写真が印刷物とかにいろんなものに変わった表面的な結果しか見てないから。自分で見たものがこうなる、というギャップが面白いと思えるのは、フィルムで撮っているから感じることができるのだと思います。若い世代の写真家のデジタルの写真は、質感とか風合いじゃなくて、アイデアだけにフォーカスされていることが多いけど、昔の写真家には質感も風合いも、さらにはアイデアもある。それをピカソみたいな絵にしたいと思ってプラチナプリントに仕上げていたことも考えると、昔の人には適わない。程遠いですよね。

Primarily in portraits, I have to understand the texture, the hair style, form, what kind of body this person has, how is it formed, and then based off of that, the camera is placed… If all of those are not captured, it does not become a portrait. My parents’ home was a photo studio and around second or third grade, one day my father brought home a trophy for some photography prize. I casually thought that something good must have happened, but when I take the time to remember the prize winning photograph, the subject was an old man wearing a beret so his skin had this texture, and my young heart remembered that he wore a medal on his chest. In my twenties when I first started taking photographs, I photographed all kinds of things along with portraits, but when I thought about how to view things like fashion, advertisements, or commercials, I was raised in a photo studio, so I felt it was natural to continue to take portraits. Something I have always felt is that a photograph is truly when the one subject in the photograph appears photographic. If you pursue one thing, like the quality of the skin, or the form, or the person’s expression in their eyes, to be shown properly, I noticed that it raises the photograph’s completeness greatly. For instance in Irving Penn’s cigarette series, a cigarette someone smoked thrown on the ground in the Fifties, you sense its different backgrounds, it is shown with its proper texture, and there is nothing that gets in the way including the lighting.

And to Avedon’s Marilyn Monroe, the reason he chose the photograph with the emptiest eyes, I think because no one has seen that side of Monroe. I am always thinking about those things. Of course in your work, you have to join multiple elements together and then incorporate them, but fundamentally I think it is good if portraits become that. Bones are associated with many of those photographic elements. For that meaning, bones have given me the chance to think about many things. Just changing the lens or the angle makes it look different, and the time I spend examining the bones as the feature in my study is very exciting. Bones are not human, but I think it oozes character as the subject.

There is something that I have realized over the years. I always intend to work while imagining everything from the moment before shooting to completion, but there is a sort of photographic magic from when I see it with my eye and when it gets printed and it becomes level. The beauty of the details of photographs that only analogue can produce entirely surpasses the parts that I imagine and is magic. I think about a lot when I am shooting, but it exceeds that idea. That is the beauty and charm of analogue, but digital has none of that. Analogue lets you enjoy photography while believing the magic. For digital, however close it is to analogue, as a photographer that numerical work is the least interesting. (Laughs) When it is analogue, like depth, you wonder about all kinds of things as you look into the viewfinder and take photographs, but I have a feeling that there are surprisingly not many people who share that excitement of it changing into something two dimensional. That is because they have only seen the superficial result of a photo changing into different printed items. I think that you can enjoy the gap of what you see becoming something else, when you shoot with film. The young generation of photographers’ digital work, often focus on the idea, rather than the texture or impression of it、but photographers in the past they have the not only texture and impression, but also the idea. So thinking how you finished with a platinum print wanting to make it look like a Picasso painting, it does not really suit the people from the past. It is not even close.

Interview & Text by Hiroshi Kagiyama / Translation by Ami Shibasaki

1967年長崎県生まれ。祖父と父が構えた写真館で生まれ育ったことを背景に、写真家の道に進む。約20年にわたり、ファッションやアーティストをはじめとしたポートレイトを中心に、エディトリアルと広告で活躍する写真家。ラフォーレ原宿の広告にて、2011年、2012年、ニューヨークADC賞銀賞、APAアワード2013年広告作品部門経済産業大臣賞を受賞。

Born in Nagasaki prefecture in 1967. Chose the path of photography, being born and raised in a photography studio belonging to his father and grandfather. For about twenty years, a photographer working in editorial spreads and advertisements, focusing on fashion and portraits of artists, etc. Laforet Harajuku advertising is the winner of various awards such as New York ADC Award -Silver prize- in 2011 and 2012, JAPAN APA Award of advertising -Minister Prize of Economic, Trade and Industry- in 2013.